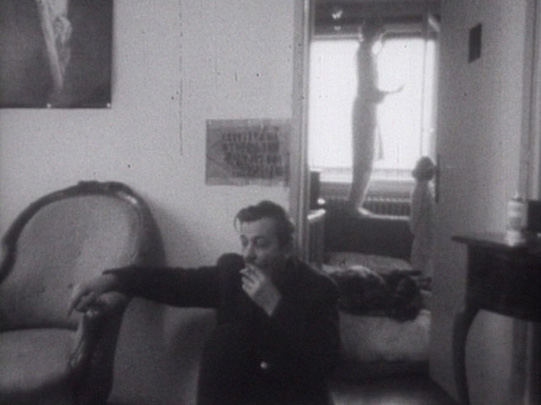

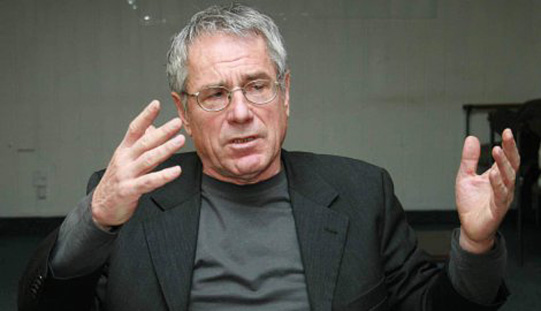

Among the many anecdotes for which Želimir Žilnik is well known, there is one involving a discussion he had, sometime in the beginning of the 1970’s, with Ivo Vejvoda, at the time one of the leading Yugoslav diplomats and communist intellectuals. Vejvoda told Žilnik that it was unfortunate that his films focused so much on the 'lumpenproleteriat', which he called “a regressive force without class consciousness". This remark was typical for the criticism accusing Žilnik of painting a “black” picture of the Yugoslav society which was ostensibly flourishing in the wake of the political and economic reforms of the 1960’s, an accusation to which he bluntly responded by making a film which he literally titled Black Film (1971). Žilnik picked up six homeless people from the street and brought them into his home, not only to share the warmth of his middleclass apartment, but also to actively participate in making a film about their situation. Black Film stands as the quintessential example of Žilnik’s work, which tends to focus on the lives of vagabonds, swindlers, tinkers, beggars and bohemians, those who were in the Marxist tradition dismissively referred to as the 'lumpenproletariat', generally depicted as an inert mass of marginal and reactionary vulgars, an unredeemed and unregenerate underclass which didn’t play any structural role in the construction of socialism. This blackness then, which was so characteristic of the 'black wave' cinema of the time, can be associated with the indication of this uneasy contradiction between those who were considered as true proletarians and their degenerate close cousins, all of which were allegedly unable to grasp the political reality of their own situation. It can also be related to the unveiling of the notorious gap between the utopian promise of knowledge and salvation on one hand and the reality of poverty and inequality on the other. But the blackness can just as well be implicated on cinema itself, this art form which unsuccesfully used to claim to have the power to change social reality. “They left us our freedom”, Žilnik wrote in a text accompanying a screening of the film, “we were liberated, but ineffective”. In spite of this self-reflexive critique, Žilnik stubbornly persevered in making films, even up to this day. The political landscape might have changed, but not the filmmaker’s attitude, which remains loyal to the uncovering of the difficult legacy of socialism and the predicaments of those who were once called 'lumpen', who are today said to be included but hardly belonging.