Guest Program - The Clock

The Clock, or: 89 Minutes of “Free Time”

A program curated by Alexander Horwath

This program is a somewhat surreal — or childlike — attempt at telling a story of the 20th century.

In a more serious vein, it relates to three different notions of cinematic temporality: it talks about leisure or “free” time (a realm of life usually regarded as the province of movie-going); it addresses “the time of film” (a past era that also produced new concepts of history and memory, both of which are now becoming more tenuous by the nanosecond); and it celebrates our imprisonment in “film time” when experiencing a theatrical projection — the distinct duration of a film, its irrevocable passing at a specific pace of X frames-per-second.

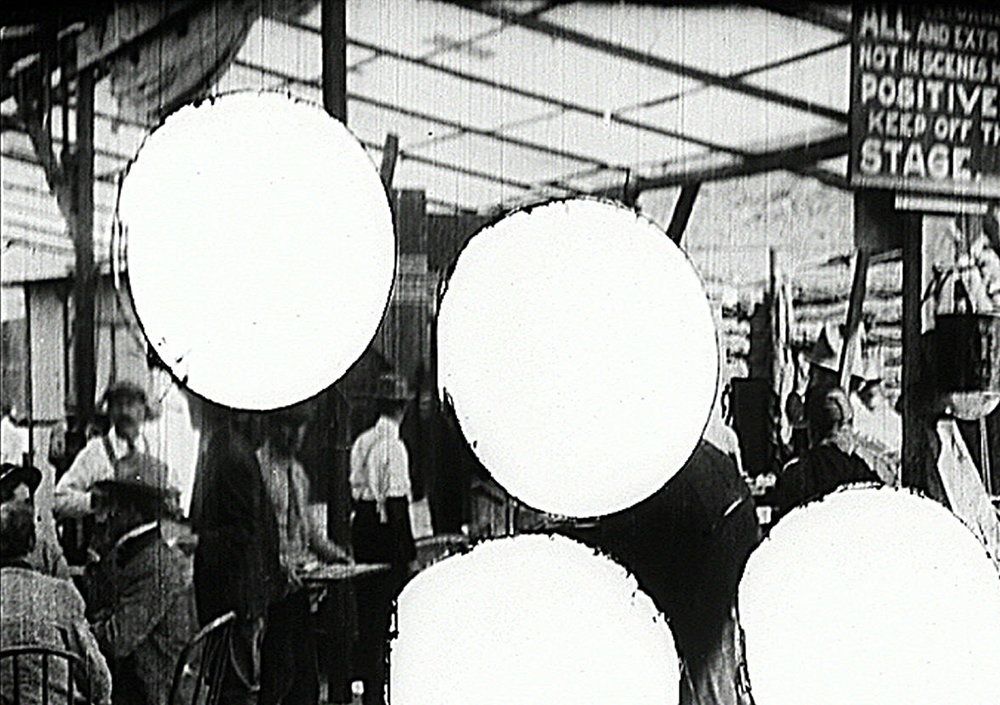

Film is a clockwork, a metaphor that was given some publicity by the most talked-about non-film of the last decade, Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2011). As opposed to the latter, however, the works in this program have some relation to life: they end. Before doing so, they exude madness, mystery and joy at a rate of 16, or 18, or 24 times per second.

Another way of looking at this film selection is through the eyes of Amos Vogel, born in Vienna in 1921, who passed away in New York in 2012. I hope that the program can also serve as a tribute to Amos. Among his many achievements in film culture was a new approach towards placing films with each other in an evening’s program, freed from their traditional grouping according to era, genre, aesthetic, etc. In addition, the Vienna amateur film shown here — Ha.Wei. March 14, 1938 — is a document of the historical moment that turned 17-year old Amos Vogelbaum into an exile. (Alexander Horwath)

In the presence of Alexander Horwath

Supported by Österreichisches Kulturforum Brüssel

Special thanks to Austrian Film Museum

Some notes on a “Utopia of Film”

In December 1964, distressed by the lack of awareness (in Germany) of what the film medium had achieved in the past, Alexander Kluge wrote his essay Die Utopie Film: "If literature did not exist, and if instead of literature we had only the annual catalogues of publishers' new releases, no one would be able to imagine the utopia which is contained in the works of Melville, Balzac, Flaubert and Döblin; Joyce would be altogether unimaginable. When it comes to films, imagination finds nothing to lean on in history. The Utopia of film, or in other words, the idea that there could be something other than the unsatisfactory momentary present of cinema, has hitherto not been able to unfold. The promise that film history contains is still basically unknown."

Since that time, the overall expansion of film culture (film museums, festivals, new distribution channels, broadcasting, etc.) has contributed to an improvement of the situation, at least in terms of quantity. But there has to be more doubt than ever whether "the promise that film history contains" (Kluge) is really being perceived. Much remains inaccessible, and much exists only in a form devoid of context, shorn of essential elements and of film’s somewhat “resistant” temporality. This is why there is still a need to bring forth the little-known promise of film, and to do it in a way that keeps this promise redeemable – alive, usable, political in essence. I would venture that the current modes of fitting moving images into each and every domain of life and of aligning the “filmic” with the dominant temporal structures of society represent the opposite of film’s utopia – and also the opposite of the “heterotopic” qualities of cinema as described by Foucault.

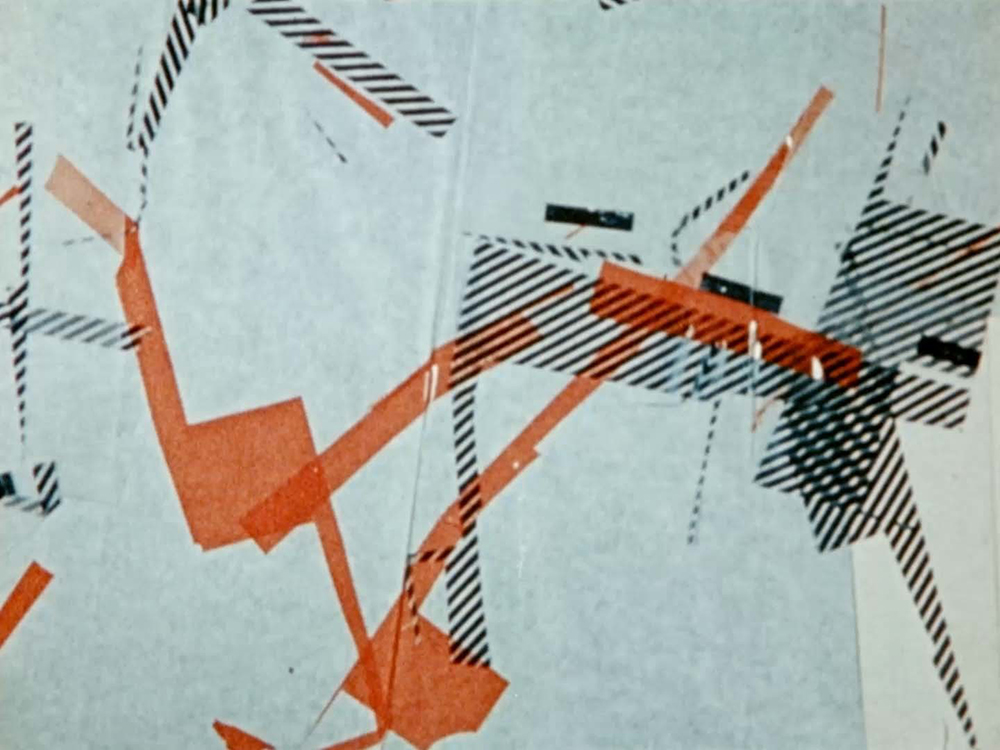

Beyond this basic premise, the utopia of film also resides in an understanding of cinema which allows its vastly different forms – and their vastly different kinds of intelligence and beauty – to co-exist in a productive manner. This notion doesn’t just measure cinema by the stick of longform narrative movies (as most cinephile discourses do, not to speak of the rhetoric employed by the film industry). If one truly engages with the various types of filmmaking – “feature film”, “documentary”, “experimental film”, “short film”, “home movie”, “newsreel”, “artists film”, “advertising film” etc. – it becomes apparent that such strict compartmentalization is only a means of keeping the transgressive potentials of film at bay. Anyone who doesn’t just want to copy the industrial “sales pitch” that has tried to define cinema from its very beginning can easily arrive at such an understanding. Film was not just a new art form; film was not just a new type of spectacle for consumption; film was not just a new language for the production of ideology; film was not just a new sort of historical document; film was not just a new scientific tool to better penetrate the visible world: As a new cultural technology of the industrial age, it was all these things at once. And its legacy is still with us, in each and every great film that comes along (no matter if it attaches itself to only one of these functions).

In order to pass on this legacy to the future, it will be necessary to keep the “impure genetic constitution” of cinema intact, just as it is necessary to keep the technological-aesthetical parameters (its “genetic code”) intact by which the medium made its impression on the world.

* * *

And yes: the utopia of film is the utopia of a reality which refuses to be staged (Jean-Louis Comolli); but it is equally the utopia of an artifact which refuses to be mistaken for reality.

(Alexander Horwath)