Breaking Sacred Ground

“Film is, in this culture — especially for Black people — the last solid white bastion of the society. It’s the one area where we have an inferiority complex. The whole myth of Hollywood, the way film functions in this culture, has succeeded, artistically, in brainwashing all of us... Film is the largest, most powerful, most potent myth. And we have not thought about how that myth applies to us. We don’t believe it applies to us. So, we can’t believe ourselves as filmmakers when we talk about John Ford, Huston, Betty Davis, John Wayne, and so forth. Hollywood is the one mythical world that America created! The Gods and Goddesses of America are film stars! They’re the Greek mythology of America, and we don’t know who we are in that mythology. How can we talk about picking up a camera when there is a sacred imaginary mythology around film, around Hollywood, around movies, and we would be breaking sacred ground!” — Kathleen Collins, 1980

“There are times when the white critic must sit down and listen. If he cannot listen and learn, then he must not concern himself with black creativity... I want to say that it is a terrible thing to be a black artist in this country — for reasons too private to expose to the arrogance of white criticism.” — Bill Gunn, letter to The New York Times, 1973

In a tribute to the singular actor, playwright, screenwriter, novelist, and filmmaker Bill Gunn, Ishmael Reed wrote: “Gunn used the stage and the page to rail against the Movie Industry forces, not in the manner of the diatribe, but in the style of the samba and the bossa nova. With subtlety and with wit. He was too deft for the obvious. Too complicated. Too odd.” When he passed away in 1989, Gunn had directed only three films, all with problematic histories. Stop (1970), one of the first studio films to be directed by an African-American filmmaker, was shelved and remains locked in Hollywood’s vaults. Ganja & Hess (1973), which Reed called “what might be the country’s most intellectual and sophisticated horror film,” was heavily recut, retitled, and reissued without Gunn’s approval. Personal Problems (1980) was an experimental, shot-on-video soap opera that had limited showings on public television and at scattered venues before disappearing for nearly forty years.

Why is it that the work of so many African-American filmmakers seems to remain hidden from history? “Isn’t the canon debate really about identity politics?” filmmaker and critic Peter Wollen was asked over two decades ago. To which he replied: “All I want to claim is that when we set out to revise the canon, we should be able to argue our position on aesthetic grounds,” giving the work of Bill Gunn as a prime example of films “we should look at again.” This programme is a modest invitation to “look again” at a selection of African-American independent films that have sadly gone overlooked or underappreciated for too long.

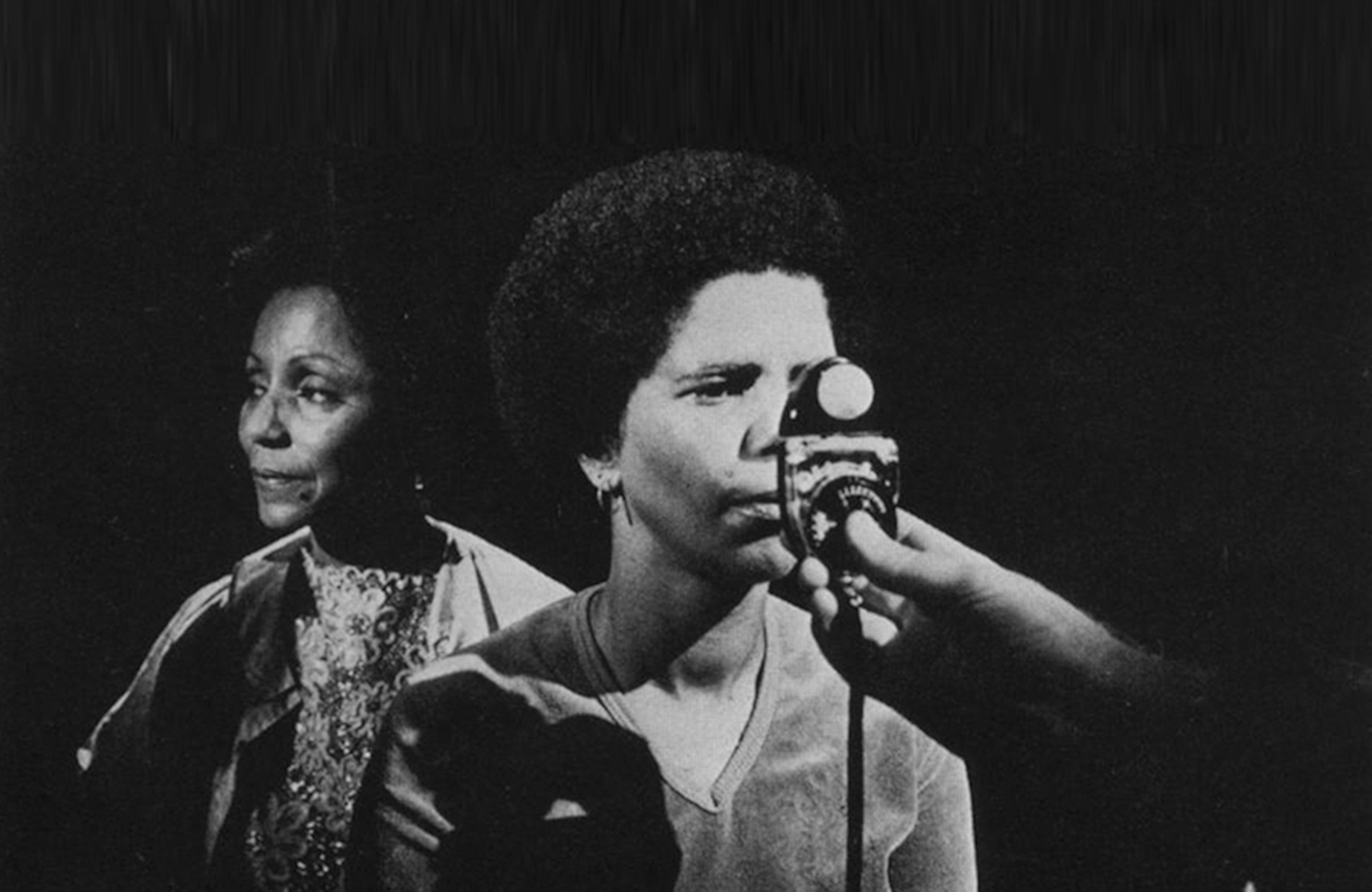

Following the programme dedicated to the work of the so-called “LA Rebellion” movement at Courtisane Festival 2015, this selection will focus on manifestations of independent filmmaking emerging from the East Coast of the US, particularly from New York. Most, if not all, of these works have been largely invisible for decades. This was notably the case for William Greaves’s endlessly revelatory meta-documentary Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, filmed in 1968 and completed in 1971, but only shown publicly two decades later. At that time it became a new entry in the annals of film history, but perhaps it wasn’t the rewriting of them that it should have been. The same can be said about the films of Kathleen Collins, a playwright, writer, director, and educator who worked with Greaves on Symbiopsychotaxiplasm and the groundbreaking television show Black Journal, before embarking on her own cinematic ventures. She completed two films, most notably Losing Ground (1982), which was one of the first feature-length films produced by an African-American woman. At a time when the film industry predominantly identified “black experience” with tales of poverty and crime, this thoughtful, understated film about the interior passions and affections of a woman in a troubled marriage received little notice in the US, until it finally had its first theatrical release in 2015.

Some of these films were initially responded to with curiosity and acclaim, at least in Europe. Ganja & Hess premiered during the Critics’ Week at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, where it received a standing ovation and the critics’ choice prize, but was largely dismissed by most American critics and quickly lumped into the category of blaxploitation films. Personal Problems had its world premiere at the Centre Pompidou in 1980 and was reportedly described by a critic as a soap opera as Godard would have done it; but due to industrial obstructions, the self-described ‘Black soap opera’ was never able to reach a wide audience. Sidewalk Stories (1989), Charles Lane’s tender homage to Chaplin’s The Kid, won the Prix du Publique in Cannes, where its 12-minute ovation set a new record, but receded from view after a limited run. Luckily these three works, too, have been given a new life thanks to recent restorations.

Other films, however, are still awaiting the consideration and appreciation they deserve. In 1989, a piece in Cahiers du cinéma read: “Twenty years after Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess, the intellectual Black American cinema returns with the remarkable Chameleon Street”. But despite garnering the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and having its remake rights purchased by a major studio, Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s witty and sardonic critique of race and class relations vanished as fast as it appeared. Two years later, the same Sundance prize was won by Camille Billops and James Hatch, whose emotionally raw and uncompromising autobiographical documentaries about domestic life remain all too unseen to this day.

So let us look again at some of the films that have attempted to break the “sacred imaginary mythology” that Kathleen Collins spoke about. Let us look closely at Fronza Woods’s sensitive portrayals of everyday struggle and resolve, and Edward Owens’s poetic portrait studies of his mother and her circle, both of whose filmmaking careers were regrettably short-lived. Let us look again at the work of all those who might have been considered too deft, too complicated, too odd. For, perhaps more than ever, we need to cherish and hold on to that very notion that critic Serge Daney once reserved for the films of Bill Gunn: “unclassifiable”.

Thanks to Jacob Perlin, Louise Archambault Greaves, Brian Belovarac (Janus Films), Jonathan Hertzberg (Kino Lorber), Amy Heller & Dennis Doros (Milestone Films), Nora Wyvekens (Carlotta Films), Ed Halter, MM Serra (The Film-Makers’ Cooperative), Edda Manriquez (Academy of Motion Picture Arts), Amy Aquilino (Women Make Movies), Eugene Lee & Roselly Torres (Third World Newsreel), Céline Brouwez (Cinematek), George Clark, Wendell B. Harris Jr.